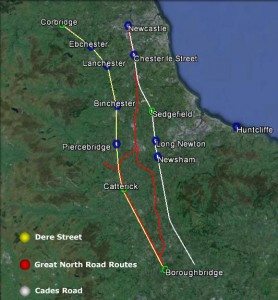

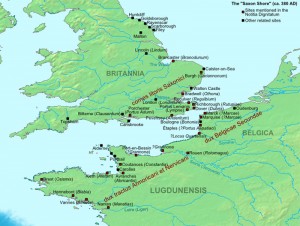

The late Roman coastal defence called the Saxon Shore, stretches from the English Channel coast, around East Anglia, and then intermittently northwards ending abruptly at Huntcliff just south of the River Tees, a sort of Roman version of the WW2 Atlantic Wall apparently to deter against 4th century seaborne incursions.

As per usual with archaeology it is somewhat of a gilded lily, because the current archaeological evidence for any sort of cohesive defensive system is patchy indeed, and when it comes to hard evidence we have a mixed bag of sites too far apart to be any sort of cohesive integrated system, with few literary references.

What exists in physical terms are a series of substantial forts built or reoccupied lining the coast from the Isle of Wight around the Dover strait and Thames estuary to Caistor on Sea in Norfolk. After Caistor we have an apparent 100km coastal gap before the fort at Brancaster on the edge of the Wash, then a 150km coastal gap through Lincolnshire to the postulated naval base at Brough on Humber some 50km up the Humber Estuary. The first of the North Yorkshire Coast signal stations is at Filey 130km along the unprotected east Yorkshire coast and Humber estuary, with finally a 60km coastal gap between the most northern signal station at Huntcliff and Arbeia at South Shields on the Tyne, a Roman naval station at the end of the occupied forts of Hadrians Wall. A total distance of some 440km of undefended coastline with a dozen major river estuaries, not so much a Saxon Shore defence, more like modern EU Border Control.

Of course it is not that simple!

Coastal erosion in Norfolk, Lincolnshire and East Yorkshire are quite likely to have swept away defences over the intervening 1600 years, however coastal erosion is perhaps not quite as convincing for the apparent absence of sites in Durham with its magnesium limestone cliffs. With a general elevation above OD of about 35-40m between the Tees and the Tyne, there should be some evidence to find. The apparent absence of coastal Roman sites in Durham may well be the legacy from extensive coastal deep coal extraction over recent centuries, and the extensive dumping of carbiniferous coal waste over the shoreline and the cliffs, as well as the notorious sea dumping via trolley systems as evidenced by the film ‘Get Carter’.

Ignoring minor estuaries we have 1000km of coastline between the Isle of Wight and South Shields. What we have surviving and discovered are a series of manned forts stretching from the south coast upto Brancaster in Norfolk, apparently without any signal stations or smaller forts between them to provide warning of incursions in the 20km + gaps between them, and a series of signal stations in Yorkshire between 11km and 20km apart, apparently without any forts in the vicinity to warn.

To use an old north east term. ‘There’s rabbit off somewhere’

It is for others to look for evidence for small forts and signal stations in the Saxon Shore south east, my research is looking for the missing military sites that give some coherence to the existence of the signal stations. As it stands the 5 stations were probably manned by 10 men each, providing a force of 50 men to defend a 75 km coastal strip, who with our current narrative were probably reduced to lighting fires, shouting rude words and baring their backsides at the invaders from their cliff top towers to try and scare them off.

The North Yorkshire Coast

The North York Moors (NYM) plateau stretches west to the Vale of Mowbray, north to the edge of the Tees Valley, and south to the Vale of Pickering. Unlike the nearby Yorkshire Dales which gradually lose elevation as they leave their watersheds, the NYM are a high plateau. The highest point of the NYM is 450m OD reducing to around 250 to 300m OD across most of its area before dropping down steep scarps 200m in the space of 2-3km to the rivers and vales below.

The North sea coast is no exception, from Saltburn in the north to Scarborough the sea cliffs of the NYM plummet near vertically into the sea. The highest point at Boulby is some 203m(609ft), which can be put into perspective against the notorious Beachy Head, the highest point on the white cliffs of the channel coast, which at 162m (531ft) is a mere pussy cat of a sea cliff in comparison.

With such massive cliffs in Yorkshire why did the Romans need defences there?

Whilst the sea cliffs are formidable they are also serve as an eastern watershed for the moors, with several natural harbours and bays along their length from Skinningrove in the north through Staithes, Runswick Bay, Whitby, Robin Hoods Bay, Scarborough, Filey to Flamborough in the south. It is these natural harbours that perhaps offer us a clue to the purpose of the signal stations.

There are two schools of thought.

- They were monitoring the movement of coastal traffic, but to what effect, There was presumably trading up and down the coast for centuries before the signal stations were built, with apparently no reason to monitor the coastline or the coastal harbours. After the abandonment of the fort at Lease Rigg and camps at Cawthorn in the late 2nd cent, we have a near 200 year gap before military sites reappear in the form of signal stations. If we consider the signal stations as part of principally a naval operation, and even if we assume signal stations extended through Durham and down to Brough, how could they offer any defence or warning against an incursion along the coast, or inland through a major river like the Tees.

2. The second school of thought makes an assumption that the signal stations signalled inland to a garrisoned position for support, with the fort at Lease Rigg above Whitby as the oft quoted fort of choice. The problem with this theory off course is that the signal stations came into existence post 350AD, and the latest date that can be currently ascribed to the fort at Lease Rigg and the camps at Cawthorn is in the region of 180AD. Even the Roman provenance of Wades Causeway has been questioned in recent research by Historic England. If the signal stations were signalling inland two hundred years later, it would seem logical to expect them to re-use or expand these known sites with existing defences, yet that does not appear to have happened. The nearest known contemporary forts would be at Malton some 32km away, and York and the line of later forts along Dere Street some 50-60km away, and that is as the crow flies. A large garrison at a fort at Lease Rigg could in theory contain an incursion at Whitby, Staithes, Runswick Bay, Robin Hoods Bay, and Skinningrove, but these sites are between 10km and 18km away as the crow flies, it would probably take half a day for a unit to mobilise and get to Whitby 10km away, not exactly fighting them on the beaches.

Summary:

If we discount 1 and 2 for lack of supporting archaeological evidence, then the only working theory that can be arrived at is that the signal stations were part of some linear coastal defence in depth using a series of garrisoned forts, on or in close proximity to the coast, supported by early warning from the signal stations on the high cliffs, and close enough together to allow for garrisons to work together to provide a larger force to deal with any given incursion,. whilst having the signalling ability, either visually or by messenger to communicate to the larger forts and fortresses inland.

If you have read so far and come to the conclusion that here we have another airy fairy theory, ignoring the millions of words of academic research on the late Roman Army, academic research perpetually based on re-analysis of the existing data.

The status quo is ridiculous, there has to be other type/s of Late Roman military site of non standard design, or no design, bigger than a signal station, but smaller than an auxiliary fort.

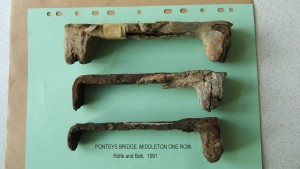

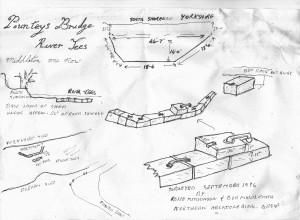

One of the central themes of our project is revisiting all the regional AP archives with a view to identifying sites hiding in plain view in the < 100m x 100m(1Ha) range , that had the potential for post Roman use as small enclosures. Our project is currently locating such sites within the Tees Valley, and currently has 9 candidate sites for further field investigation. One has had a small investigation of a ditch section, where we found a ‘V’ shaped ditch, a few sherds of early Roman pottery and 100 pieces of 3rd and 4th century Crambeck and calcite gritted wares. This work will continue over the next couple of years