Pounteys Bridge Investigation

Rolfe Mitchison and Bob Middlemas

1991

( additional Cades Road research by John Brown)

Pountey’s Bridge and the Tees crossing point of Cades road is the classic chicken and egg scenario. An enigmatic roman road lost to history needing a crossing point, and a bridge looking for a road to cross it, put the two together, a touch of imagination and everything is a possiblity.

Pountey’s is but one manifestation of the name which simply means Pons(bridge) and teys(Tees). Bridge of the Tees.

- Pountey’s Bridge

- Pontasia 1196×1208 Surtees III 228

- a Ponte Teyse c.1200 Surtees III 229

- ponti de Puntays early 13th Spec

- Pontayse 1235, 1235×6 Ass

- Pountays 1379 Surtees III 242, 1380 Surtees 228

- Pountese 1426 Surtees III 228

- Pountes 1512, 1514 IPM

- Ponteys 1552 Surtees III 232

The earliest name and reference is circa 1200, and with Leland failing to mention it in the middle of the 16th century it would seem by his time it had already gone out of common use. Perhaps a more accurate indicator of its demise, can be gleaned from the known presence of a hermitage on the bridge under the control of the prior of Durham, who made the last appointment to this hermitage in 1426, after which there is no further reference

That there was a bridge at Middleton One Row there is no doubt, and a bridge that seems to pre- date the bridges at Yarm built by Bishop Skirlaw in about 1400, and the current bridge at Croft also built in the 15th century to replace the earlier wooden bridge destroyed by floods. The question is what evidence is there for linking Pountey’s bridge to the Roman period as a crossing point of Cades Road(Margary 80a), and when was the link made.

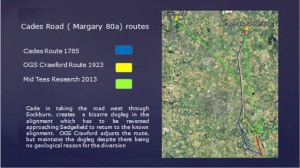

Cade’s Road(Margary80a) is named after John Cade of Gainford, an 18th-century antiquarian who in 1785 proposed its existence and possible course from the Humber Estuary northwards to the River Tyne, a distance of about 100 miles (160 km). Although evidence exists for such a road on parts of the proposed route, particularly through North Yorkshire, there is considerable doubt regarding its exact course and where it crossed the Tees. The road’s Roman name is unknown, although Cade referred to it as a continuation of Rycknild Street.

Cades route begins at Brough-on-Humber the site of a ferry, a Roman fort and civilian settlement (Petuaria) alongside a major Celtic settlement. He suggested that it ran northwards through Thorpe le Street and Market Weighton, before gradually turning westwards (possibly following the line of another Roman road) until it reached York (Eboracum). From York it continued northwards, skirting the edge of the Hambleton Hills towards Thornton-le-Street near Thirsk, and then north just to the west of the massif of the North York Moors. Approaching the Tees the 12km extant alignment of hedgelines and country lanes evaporates into thin air just 800m from Fardeanside Ford a crossing point into Newsham in the parish of Egglescliffe one of the principal crossing points of the Tees, even after the building of the road bridges at Croft and Yarm. After crossing the Tees Cades route takes the road north to Sedgefield, Durham, Chester le Street, before finally terminating at Newcastle.

It is at this point on Cades deliberations, where common sense and logical thinking seem to have left the building, in preference for the if’s, but’s and maybe’s of antiquarian thought.

John Cade was a local man from Gainford, and the area along the 100 mile route he knew most intimately was where he was now trying to solve a conundrum. Accepting that he was party to the view that Roman roads were generally straight between given points reflecting the topography of the landscape, logic would have suggested that crossing the adjacent ford, would allow the route to continue in a more or less straight line towards the point where the route becomes evident in the landscape again at Sedgefield. The problem for Cade was that a crossing at the ford was not supported by evidence of archaeology, no Roman camp, no earthworks, and perhaps more importantly no clearly defined straight alignment to the north.

Did Cade therfore jump at Pountey’s bridge as his crossing point?

Well no he didn’t!

Cade didn’t choose Pountey’s because he presumably knew that in 1785, there were numerous mentions of Pountey’s bridge as being medieval, it was not until the 1820’s, that for the first time the bridge is mentioned as Roman.

Cade also had another candidate, just 2km to the west in the longest loop of the Tees that extends some 4.5km from the median line of the river south into the North Riding of Yorkshire lay the ancient site of Sockburn(Soccieburg). A defended ancient site by its name elements, the site where all the new Prince Bishops would formally enter the county of Durham, the site of the famous Sockburn Worm legend, an ancient church with Viking hogbacks and Anglo Saxon crossshafts aplenty. Sockburn, together with maps already ancient by 1785 showed a road north out of the peninsula joining with the straight road north to Sadberge at Middleton St George. Cade presumably had enough circumstantial dots in his mind to join them up and neatly extrapolate the site at Sockburn back to the Romans. In doing so Cade forced his alignment 2km to the west of its route through North Yorkshire creating a dogleg. A single dogleg is perhaps not a problem, and is common on roman road alignments, the problem for Cade was that as he approached Sedgefield, he had to force the road back to the East by 2km to return to the alignment in East Park. This diversion created a double dogleg, with not a pimple in the landscape to justify it, clearly against all the engineering practices common to the laying out of a roman road alignment.

Perhaps we should not be too hard on John Cade, he was after all working without the modern benefits of good maps and aerial photographs., we can perhaps be less generous with those who came later.

To anybody considering field research in archaeology, the logic of Cades double dogleg is a perfect archaeological example of putting two and two together and making five. However Cades alignment set the baseline of the alignment, which in major part survives to this day. Cades route was subject to criticism within a few years of him publishing it, but it was nearly 150 years before an alternative alignment at the Tees was suggested by OGS Crawford of the Ordnance Survey.

In the early 1920’s, probably based on 100 years of local folklore and surrounding the romanisation of Pountey’s bridge in the 1820’s, OGS Crawford suggested an alternative alignment. The intervening century had generated claims of a motte north of Pountey’s being a Roman camp, with perhaps another Roman camp at Sadberge in the ‘roman’ field, he needed to look no further than Pountey’s Bridge. Without any more actual evidence than Cade, he suggested the road continued in a NNW direction and crossed at Pountey’s, before returning to Cades alignment. Crawford although reducing the dogleg to the west slightly, like Cade did not address the return dogleg approaching Sedgefield,

Despite the passing of 250 years since Cade, and despite numerous investigations, no evidence of Rome has been found at Sockburn or Pountey’s or on the alignment upto Sedgefield, apart from a few random finds.

Subsequently Crawfords route, including Pountey’s was adopted wholesale by Margary in his definitive book on Roman roads, but still nobody questioned the bizarre logic of the doglegs, whilst 800m away across a simple ford, hiding in plain view was a Roman military site and settlement on the north side of the river, opposite the confirmed southern alignment, and exactly where logical thinking, topography, strategic value and common sense dictated it should be.

As the specialised divers in the amateur Northern Archaeology Group , we led an investigation at the site of Pountey’s Bridge, with the aim of locating any remaining structure, and hopefully dateable artifacts to support the argument that Pountey’s was Roman.

Bob and I first got interested in Pountey’s Bridge in early 1991. This was due to the diligence of a Billingham historian called George Preece, who devoted many hours researching the subject. George told us that the bridge foundations were still visible in the river in 1823, and asked if we could locate them. He had already secured permission from the land owner in advance.

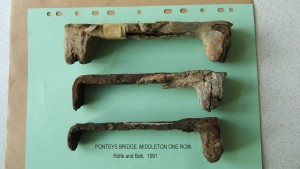

Our first dive was on the 4th May 1991, when we spent 5 hours searching approximately 100m of river bed. We knew we were in the right area when we found pieces of worked lead, followed by a chisel, then an iron clamp, clamps of this type were used to hold massive bridge stonework together, the lead was then poured in molten solidifying the joint between the iron clamp and the stone. The lead would be chipped out with a chisel when the bridge was being dismantled.

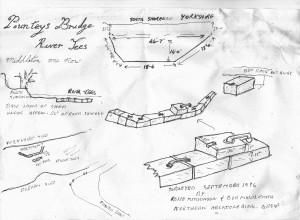

Our next dive on the 8th June 1991 produced a second iron clamp, and after digging down 300mm in the gravel bed adjacent to the southern bank, we uncovered the top of a large worked stone. This stone measured 550mm D x 750mm W x 175 mm H. We were happy we had now located the remains of the southern abutment of Pountey’s Bridge, but were pleasantly surprised to discover that there was another layer of clamped foundation stones underneath this single stone.

Our next job was to find a pier, so we measured out 8m from the face of the abutment and dug down into the gravel. After digging 450mm down, the stonework of the likely pier emerged with quite an area of it still intact. The huge stones like the abutment were held together with iron clamps.

Over the next few weeks we completely uncovered the south abutment and found it to be 13.6m wide and 15m deep.

An open day was held in the September 1991, when members of our Northern Archaeology Group and the public, were able to wade across the warm river and observe the foundations, using glass bottom buckets.

After the open day, Bob and I reluctantly filled the excavations in and the bridge resumed its long sleep.

Bob and I have recovered approximately 5000 Roman coins and artefacts, plus buckets of pottery from the Roman bridge crossing at Piercebridge, in contrast we have not managed to find a single coin, artefact, or shard of pottery at Pountey’s of any period. This absence of material may be more a factor of the deep deposits of river gravels 2-3 metres deep across the Pountey’s crossing site, perhaps in the future investigating down to the the bedrock, the secret past of Pountey’s Bridge will probably be found.

The investigation whilst perhaps not confirming whether the bridge was Roman not, has perhaps provided additional evidence supporting a likely medieval date for the bridge . Traditional Roman masonry construction techniques used in large structures are alternating stretcher courses and header courses, this has the purpose of the header courses extending behind the facing stone, locking the stone face of the structure to the core structure behind, and increasing the stability of the structure as a whole. However the two courses of masonry exposed in the south abutment of Pountey’s are both stretcher courses, there is also the absence of Lewis holes in the stones for location and handling the material, also very unusual though not unknown on a Roman structure. Pountey’s Bridge was a mystery, and to some degree still remains a mystery, although we have perhaps shed some light on the issue.

Rolfe Mitchinson & Bob Middlemas.

Postscript.

Although this site is principally for research conducted by the Mid Tees Research Project, we are happy to publish other unpublished research by other organisations or individuals. If you have a piece of work gathering dust on your shelves, send us a copy either peer reviewed or not, and we will add it to the archive. It is more important that raw data is made available to other researchers, even if some of the ‘T”s and a few of the ‘I’s remain uncrossed or undotted.

Please send any contributions to: john.brown@reiverenglish.com